Power & Politics for Engineers: L8Conf, Warsaw

This is a write-up of the presentation I gave at L8Conf in Warsaw on 17 March 2025. The original presentation was replete with animated GIFs and slide transitions which don't translate well into a web page, but I've expanded the speaker notes into something a bit more article-like.

I've been working in the software industry in one way or another for over 20 years. In that time I've been part of some amazing successes, and I've caused some colossal failures. If I look back at the causes, a lot of the successes were down to the technology, but virtually all the failures were people-related.

That's the dirty secret of the software business - we like to think that what we do is hyper-logical, predictable and grounded in rigorous reality, but the actual way things work is a lot more messy. However much our tools are based on logic, what we do with them involves the non-linearity of people - and dealing with that seems to be a blind spot for many (if not most) engineers.

I'm no different. Even after 20+ years, and with the advantages of a relatively unusual background by "normal" software carerr standards and time spent actually studying psychology in the business/industrial context, I still get blindsided by organisational power structures and internal politics.

About 20 years ago I took a couple of years off to go and get an MBA, and one of the core modules on the course was Organisational Behaviour. That's a fancy title for psychology applied to the workplace - there's a massive amount of academic research been done in this area, and power (and to a lesser extent) politics are popular subjects for study. That means there's a lot of models for power structures and political behaviour, some of which are reasonably accessible to the non-specialist.

There's nothing engineers like more than models and frameworks to bring apparent order and structure to chaotic and ill-defined reality, so this is my attempt to summarise power and organisational politics as they relate to the world of software engineering by drawing on a number of OB frameworks.

Mental images of power

If I were to ask you to close your eyes and describe the first mental picture that comes to mind when you think of the word "power", there's a good change you would come up with something involving politicians or the military. Soldiers being shouted at. Horrible people coming up with ever-more inventive ways to kill each other in order to claim the throne. Or politicians lying and cheating their way into government.

Those are all certainly valid concepts of power, but the power we've thinking about is slightly different. There's (usually) less shouting and swordfighting in businesses, but companies still have power structures. The fact that there's lots of mental images that come to mind connected to the word suggests that it needs some definition, so let's start by digging into what we mean by power.

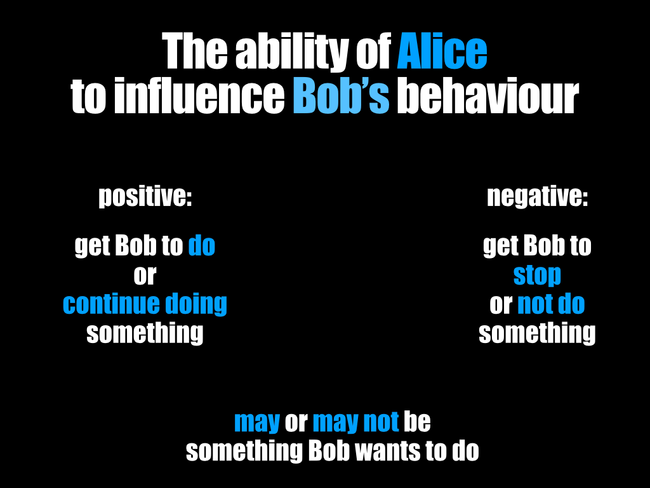

If we ignore the definitions that are based on physics and engineering - amps, watts, newton metres and so on - what we're left with is the idea of power as the ability to influence behaviour. That's a good starting point - power is the ability of one party to influence another, so it's the ability of Alice to influence Bob to do something.

That something can be in a positive sense - Bob starts, or continues to do something. It can also work in a negative sense - Bob stops, or doesn't do something. It's also worth remembering that it may or may not be something that Bob wants to do - so there's potentially an element of compulsion in the process.

Power and organisational politics is something that's fascinated psychologists and sociologists for as long as those disciplines have existed, so there's no shortage of academic research to dig into. A lot of models of organisational power and politics are dense and almost incomprehensible if you don't have a social sciences background; but there are some which can be simplified.

One of the best-known of these is the "five bases" concept developed by John French and Bertram Raven which they originally published in 1959. It categorises power into one of five types (later extended to six) which have distinct forms and applications.

There's some caveats - first of all, it's just a model. That means it's a drastic oversimplification of complex patterns of non-linear behaviour (in other words, it's trying to describe how people behave). The research that underpins the model was done in US corporations a long time ago, so the subjects involved were largely white, male, middle-aged middle management middle Americans of the mid-1950s. We need to be a bit cautious about applying the model unthinkingly to our situation - but despite the cautions, it's still useful.

I've tweaked this slightly to reflect the nuances of the software world, and added a six-and-a-halfth form of power to the end.

It categorises power and influence into the following types:

- Coercive

- Legitimate

- Reward

- Expert

- Resource

- Referent

- Social

Coervice power is power backed up by the threat of compulsion or violence. It might be one of the images that came to mind earlier - if you fail to follow the orders of the gentlemen in the image, eventually they will force your compliance by hitting you with their batons.

Fortunately it's not a form of power that you're likely to meet in the workplace, outside of some very specific situations like the military, law enforcement or the prison service. Even then, it's more likely that you'd be imposing coervice power rather than being on the receiving end.

When it comes to figuring out how to respond to coercive power, it's hard to come up with any tactic other than to avoid it. You're either in the wrong place or working for the wrong person - the circumstances where coercive power would be an appropriate approach are very hard to imagine.

If you want to use coercive power however, there's a few things to bear in mind. You have to be ready to follow through on your threats and actually use it - fail to do that, and eventually your subjects will realise that the threats are empty. There are likely to be some rules or constraints that you have to follow - stepping outside of those repeatedly is likely to lead to situations where your subjects feel they have nothing to lose by revolting or striking back. But ultimately this is a power that works by fear of imposition, so building on that sense of dread will make it more effective.

Legitimate power is derived from your position in a defined hierarchy. The gentleman in the picture is General Wiesław Kukuła, who at the time of writing is the head of the Polish Armed Services. He gets his power by virtue of his rank and position in the structure. That position entitles him to issue orders, and obliges his subordinates (outside of very specific and limited exceptions) to follow those. Effectively, he has the power to order the soldiers under his command to go to their deaths - so legitimate power is both very real, and very consequential.

The stakes may be lower in your organisation, but there will still be people with legitimate power. Requests from the CEO will carry more weight than one from an intern - the organisation chart builds an expectation that those above can issue instructions to those below. Compliance might be implied, rather than enforced in the way that orders in the military can be - but the hierarchy imposes a power structure nonetheless.

When responding to legitimate power, there are a few things to consider. Are there ways to work around it - hierarchies are often less clear-cut than organisation charts depict them. Especially in matrix organisations, hierarchical power from one level of the organisation can be affected if there are alternative or additional reporting lines which work sideways or diagonally rather than straight up-and-down.

You often have some degree of flexibility in how you respond to requests that originate from legitimate power, and that's a way of retaining some agency in the situation. And (as we'll see with the other forms) legitimate power is often influenced or even overridden by other forms of power, so it's possible you have power in other forms that you can use to influence or resist the power being imposed on you.

To fully-exploit legitimate power, you'll need to emphasise your position in the hierarchy through a fancy title - "Chief of Staff" sounds a lot more impressive than "Assistant to the CEO". Symbols are a subtle and important way of reinforcing legitimate power - think of how sumptuous robes and decorations adorn senior figures in the Catholic church, for example. And finally, because legitimate power derives from the organisational hierarchy, to be subject to it requires an acceptance of the individual's place in that hierarchy. Dissent from legitimate power is a effectively a challenge to the structure, so toleration of dissent can lead to the power's weakening.

This power works by Alice offering something that Bob wants in return for Bob's compliance. Reward power is immediately familiar to anyone who has a dog, (and perhaps even children!) Dogs respond to praise and treats, so their behaviour can be conditioned by getting them to make a mental connection between the behaviour - sitting, for example - and a "good boy/girl" and a biscuit.

Reward power isn't quite that blatent in organisations, but it's still there. Salary bumps, promotions or other tangible items like a better desk position or faster hardware are all desired rewards, so the person who controls their allocation can derive power from this.

Responding to reward power is partly a function of how much value you attach to the reward - the more you want that extra salary, the more power the person controlling it could exploit. That suggests that substitutes which are obtained elsewhere can weaken reward power. And it might be possible to get the reward from somewhere else - if the supply is substitutable, maybe the conditions attached to the reward from the alternative supplier are more favourable.

Exploiting reward power means ensuring that the rewards resources are scarce, and can't be subsituted in some way. The power can also be maximised by making sure that the link between behaviour and results is explicit.

Expert power is something that we're very familiar with as engineers - there's probably someone in your organisation who gets treated differently because of what they know, and the consequences if they weren't around any more. Alice knows more than Bob about the deployment processes, and therefore is able to push back when he tries to assign her tickets she's not so keen to work on. This is a power that can up-end the organisational hierarchy, because functional expertise is often concentrated at the bottom of the organisation chart.

Responding to expert power involves making sure that knowledge and expertise is diffused across the organisation. Crudely put, the more people who can do what Alice does, the more choice Bob has to get someone else to do it - and the less power Alice has as a result. That means preventing silos where knowledge gets hoarded, documenting processes and procedures so that it doesn't all live in Alice's head, and making sure Alice isn't a single point of failure in the organisation.

Effectively using the power is pretty much the opposite of this - become and stay a gatekeeper, hoard your knowledge jealously and never, ever write anything down. Documentation is Kryptonite to expert power.

Resource power is where Alice controls access to or use of resources that Bob needs as part of his role. It works in a similar way to reward power, but the difference is that the things that Alice controls aren't those that Bob necessarily wants so much as needing. In the Before Times when we all spent five days a week in the same office space, meeting rooms were usually at a premium - if Alice controlled their supply, she found herself in a very advantagous position when it came to getting Bob to stay on the right side of her.

This power is interesting in organisations for several reasons. It can be very subtle and difficult to spot, because resources are often literally part of the organisational furniture. It can also be structured in completely different ways to the organisation chart, so people with very little hierarchical power have significantly more power due to their effective control of essential resources.

Responding to the power can depend on how substitutable the resources are. If it's possible to hold meetings in the cafeteria, that's an alternative to meeting rooms that Alice might not control. Effective and actual control can also be different - on paper meeting rooms might be the responsibility of the building manager. In practice, they're actually controlled by her asssistant, who gains power through his ability to affect their use.

Dealing with resource power can often involve quid-pro-quo situations. When I worked in consultancy and travelled a lot, one of the best pieces of advice I was ever given was to make friends with the travel team. The occasional box of airport chocolates brought back from a trip seemed to increase my chances of enjoying the the special upgrade deals that they were able to access...

When exploiting resource power, obviously the less substituable the resources are, the more power derives from controlling access to them. Ensuring you exert control over their usage also reduces the scope for substitution, and similar to reward power, you can make the payoff for resources explicit to reinforce the connection between what you control and the results that you want.

Referent power is interesting because it doesn't rely on an explicit exchange - instead, it's powered by force of personality. By most objective measures, Elon Musk is a very unpleasant person to work for - and yet, he has no shortage of people queuing up to be part of his endeavours. That's a measure of his referent power - people want to be associated with him because of his reputation and (alleged) charisma.

This is the power that underpins influencers, whether they're encountered on LinkedIn or Instagram. It's hard-wired into human psychology to belong to groups of others, and the person with the referent power becomes the focal point around which groups can emerge. This isn't such an obvious power in organisations, but it's not unusual for some teams to be more productive because they have a charismatic boss that people naturally gravitate towards.

When dealing with referent power, it's important to be aware of the reality distortion zone effect - leaders with really effective referent power can seem to bend reality to their will. Facts and figures - objective reality, in other words - can act as a counter balance. And your wider network is also important - if what the referent leader is saying gets contradicted everywhere else, that's a signal that reality is being distorted around them.

The 1/2 of the 6 1/2 models of power is social power, and this one is slightly contentious because it doesn't fit exactly with the patterns of the others. For starters, it's not about a simple Alice-to-Bob exchange - one way of looking at social power is that there are in fact multiple Alices that have a cumulative effect on the Bobs.

The other factor is that social power is derived from customs and practices - the "way we've always done things around here" - and these can be a very powerful influence on how people behave. If you want to see this in practice, try standing on the "wrong" side of the escalator from a subway platform - there may be no signs telling you which side is the "right" one, but it's pretty obvious when you've got it wrong.

When the practices are good ones, social power can reinforce positive performance - but it's also possible that negative habits are the ones that get embedded.

Dealing with social power can feel very difficult, because peer pressure is a real and hard-to-escape force - but questioning why things are the way they are, and not settling for the status-quo can help to resist it. On the other hand, social power can be used for good by helping to ensure that it's the positive behaviours that are reinforced.

Diagnosis

Having a basic understanding of how different types of power are manifested is useful, but how do you figure out which powers are affecting a specific situation? There are a couple of techniques that can help to decide what you're dealing with.

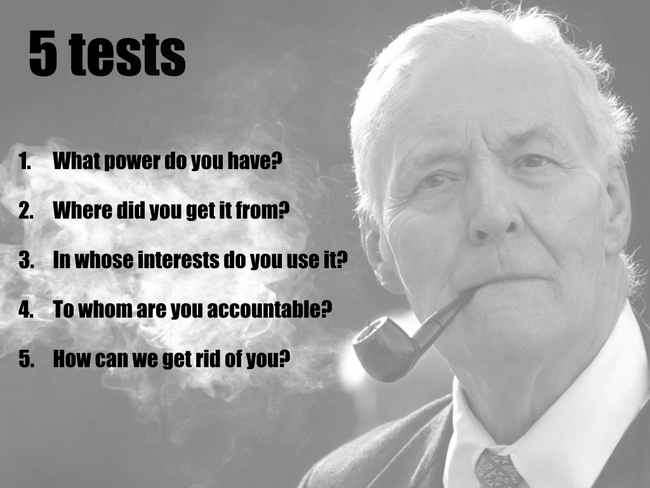

The first technique was the brainchild of a British politician of the 1960s called Tony Benn - he had the somewhat unusual characteristic of getting more left-wing as he got older, and in his later years he got very concerned about the way that political power has consolidated in the United Kingdom's system of government.

He came up with what's become known as the Five Tests of Tony Benn - they're most often quoted in political contexts, but can also be quite useful inside organisations as well. The five tests are simple questions:

- What power do you have?

- Where did you get it from?

- In whose interests do you use it?

- To whom are you accountable?

- How can we get rid of you?

The beauty of these questions is that they're holistic in the sense that they not only ask what power is being used, but also where it comes from and how it's used.

Mapping

Because real life is always more complex than simple theories, it's not surprising that power in organisations is often a blend of one or more of the archetypes, and individuals often have multiple power bases which can also change over time.

There are also interplay effects between different power holders - one person has legitimate power from their position, but they're thwarted by someone else exploiting their resource power. The permutations can be bewildering, so something that allows you to build up a picture of what's going on at an aggregate level can be very helpful.

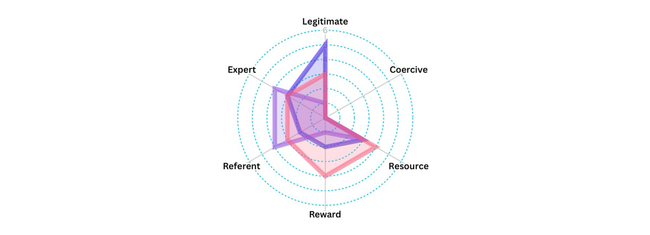

Radar plotting the power bases of multiple individuals can help to create this overview. In the diagram here, there's three stakeholders - the CEO (blue), a lead engineer (purple) and HR staff (pink). All three have zero cooercive power (thankfully!) but the CEO gains a high legitimate power score from her position in the organisation. On the other hand, she's no longer a technical specialist, so her expert power is relatively low by comparison.

The engineer scores highly on expert power, and because this is a tech-driven organisation they derive referent power as a result. They don't have a line-management role, however, so they've got very little in the way of reward power.

The HR profile is different again - they control shared resources like meeting rooms, so resource power is high - and as "owners" of the process they also have effective control over salary increments, which gives them a high reward power score.

By overlaying each stakeholder's individual power structures, it can help to build up a picture of where the apparant and actual power within an organisation lies - and armed with this understanding, navigating the power structures can become a bit easier.

Power in the real world

If you do a mapping exercise like the one above, you're going to be struck by the complexity of even the smallest organisation. When power is exercised in the real world, the result is something we know as organisational politics. That was the topic of the second half of the talk, and will be the topic of the next post.